Kazakh strongman leaves unfinished business in rush to secure legacy

Rows of bare concrete pillars stretch for kilometers along the main road of the Kazakh capital. The columns are meant to support a commuter rail line, designed to modernize the city’s public transportation and ease chronic congestion. But on a recent weekday, there were no signs of workers or equipment.

The project was one of several launched during a building spree ahead of an international expo in 2017, which brought delegates from more than 100 countries. The symbols of progress have since become stark reminders of the challenges of development: Besides the unfinished rail line, the construction of the country’s tallest skyscraper is under review after a string of accidents, and a futuristic financial center has failed to attract businesses.

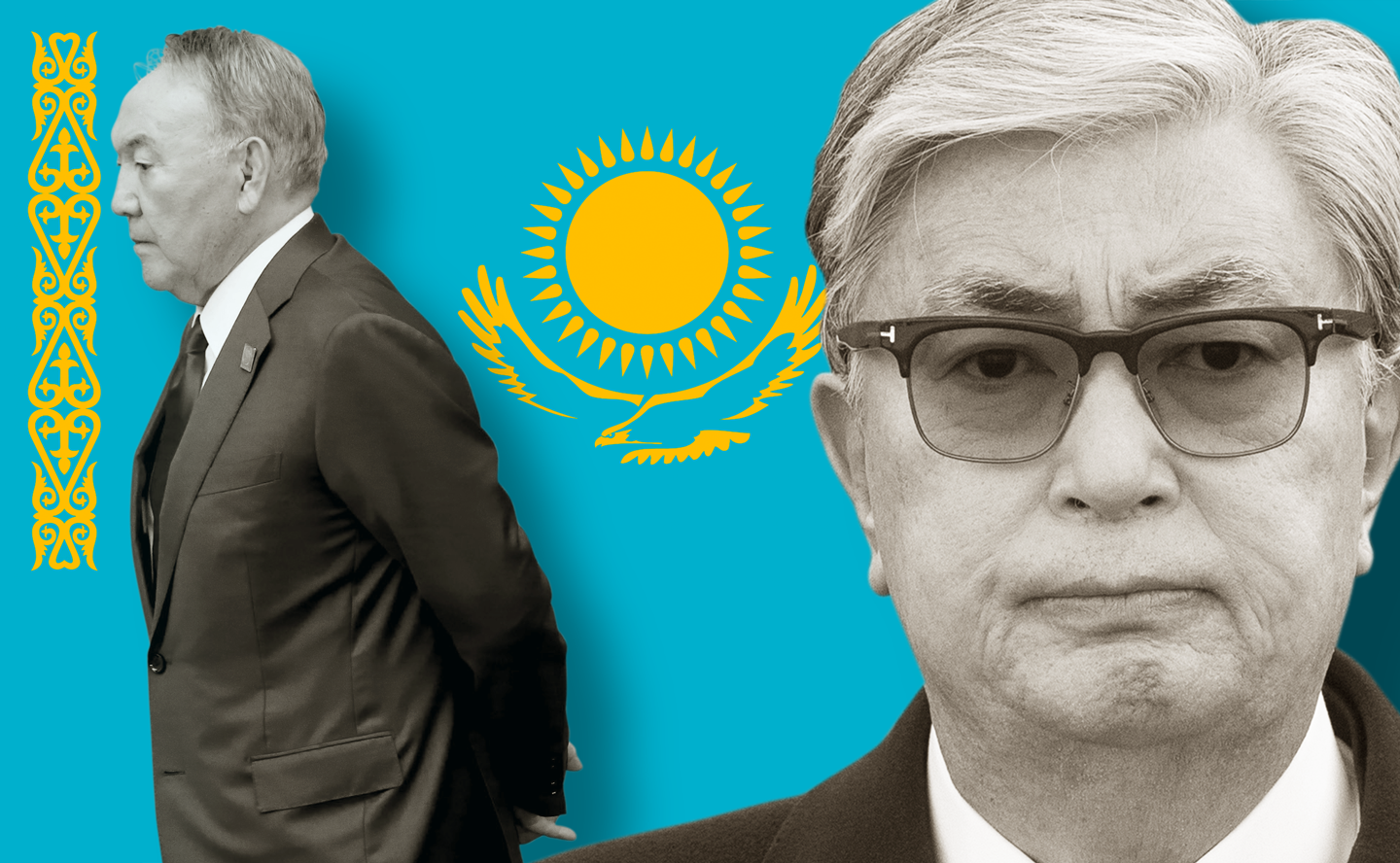

The task of seeing these projects through now falls on a new government that is being cobbled together after the sudden resignation of former President Nursultan Nazarbayev in March. The leadership faces a juggling act: harnessing the country’s ample resources and diversifying its economy while managing the interests of powerful neighbors that are increasingly jostling for influence.

Kazakhstan, the world’s largest landlocked country, sits right between China, Russia and Europe.

Nazarbayev had ruled for nearly three decades and looked unlikely to buck the trend of Central Asian leaders holding onto power as long as possible. Just last year he railed against the notion that he should relinquish his grip.

«From the early days of independence I have ruled this country and have justified people’s trust,» he said. «How many times they have said in the West: ‘Adopt democracy like we have … in America, like in the West.’ We are Kazakhs, we are not Americans, we are not Germans, we are not English. What’s wrong with that?»

He pointed to his «late friend,» longtime Singaporean leader Lee Kuan Yew, as a role model who throughout his life «was called a dictator, an autocrat.»

Analysts say political turmoil in nearby Uzbekistan — where President Islam Karimov’s death in 2016 was followed by the conviction of his daughter for extortion, embezzlement and tax evasion — was behind Nazarbayev’s decision to seek an orderly transition.

In reality, though, Nazarbayev is not going far. In accordance with the constitution, Senate leader Kassym-Jomart Tokayev was appointed his successor. Tokayev is seen as a close ally who will carry Nazarbayev’s policies forward. In a sign of loyalty, he renamed the capital Astana shortly after taking over. The new name? Nur-Sultan.

Tokayev then called an early election for June 9. He has been nominated by the ruling Nur Otan party and is generally considered a shoo-in, in a country where any real opposition is crushed. Rare public protests erupted on May 1, with demonstrators calling for a boycott of the election. Dozens were detained.

Meanwhile, Nazarbayev’s eldest daughter, Dariga, has taken Tokayev’s previous post as head of the Senate.

The stock and currency markets have been stable since the handover, signaling relief at the prospect of political continuity. But some critics warn the status quo is a path to stagnation for the country of 18 million people.

Nazarbayev is credited with putting Kazakhstan on the map. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, he used relations with the likes of Russia and China to develop the economy into Central Asia’s largest. Kazakhstan’s gross domestic product of about $180 billion is larger than the other four former Soviet Central Asian republics combined.

Kazakhstan is the world’s top producer of uranium and the fourth-largest supplier of copper. In addition, it holds the tenth-largest proven oil reserves and is a major exporter of wheat and other agricultural commodities.

The resource sector accounted for the majority of the $82 billion in foreign direct investment that flowed into Kazakhstan from 2008 to 2017, according to Boston Consulting Group. The consultancy says the country has the potential to rake in another $100 billion over the next decade.

Yet, Nazarbayev’s efforts to build a more balanced economy by diversifying away from oil and gas into manufacturing, finance and digital services — in part by courting foreign investors — are widely seen as a failure. Though limited domestic demand and high logistics costs pose significant hurdles, some business executives say the centralization of political power at the top has left bureaucrats with no motivation to deal with the headaches of implementing projects.

One executive complained that local government officials are frequently replaced, triggering fears over sudden changes in business negotiations.

Political analyst Dosym Satpayev explained the reasoning behind the «reshuffles.» «It is important for someone not to stay in one position for a long time,» he said. «If he stays too long, he might consolidate power. It is like shuffling a deck of cards.»

An inefficient bureaucracy may have been a sacrifice to maintain political stability and ensure good relations with Kazakhstan’s neighbors. But even on this front, there are signs of emerging risks. The growing clout of China has become a matter of heated debate.

Beijing has been particularly aggressive in pursuing closer ties since it launched its Belt and Road infrastructure program in 2013. China and Kazakhstan are jointly developing a container terminal at Khorgos, near the border with China’s Xinjiang Autonomous Region. The project will create a gateway for carrying Chinese goods to Europe by rail, which takes less time than by sea. A Kazakh government official said the project has generated billions of dollars in revenue.

But the prospect of China wielding greater influence over Kazakh assets and politics has sown public anxiety in recent years. In 2016, the government proposed a legal revision that would allow foreigners to lease agricultural land for 25 years, up from 10, and let entities with foreign involvement own land. This was met with highly unusual nationwide protests.

China’s strict control of Xinjiang is another source of suspicion among the Kazakh public. Kazakh authorities arrested the founder of an organization that publishes information about citizens who say their relatives have been detained near the border in Xinjiang, prompting an outcry from human rights activists.

The government has brushed off concerns that these developments could cause political instability. The issue in Xinjiang is «very exaggerated,» Timur Shaimergenov, an official at Kazakhstan’s foreign ministry, recently told foreign journalists. «In reality, it is much more simple. We don’t have any problem in Xinjiang.»

Nevertheless, Kazakhstan has obviously grown more cautious about taking Chinese money. The stalled rail project in the capital is a case in point. The local government recently announced it is considering financing the line with «internal sources» — a U-turn from previous plans to rely on loans from China.

Sources in the Finance Ministry said Kazakhstan intends to push China for a lower interest rate. If Beijing refuses, «we will find sources of funding for this project within the country,» said Alikhan Smailov, the first deputy prime minister and finance minister.

The government has insisted the development of Khorgos, too, is financed by local banks.

On the other hand, Tokayev is eager to maintain close ties with Russia, and President Vladimir Putin seems only too happy to oblige.

Moscow is grappling with a slowing economy and is nervous of losing its sway over Central Asia. To keep up with the Belt and Road, Russia in 2015 led an initiative called the Eurasian Economic Union, which created a single market with Kazakhstan, Belarus, Armenia and Kyrgyzstan.

Tokayev chose Moscow for his first official visit in April. He vowed to preserve a pro-Russian foreign policy and signaled he does not intend to deviate from his predecessor’s course. The Russian business newspaper Kommersant quoted him as saying that Russian-Kazakh ties are the «benchmark» of his country’s international relations.

Putin, for his part, said he is looking forward to «new forms of cooperation.» He suggested building a nuclear power plant «based on Russian technologies» in Kazakhstan, according to local media.

Still, while Kazakhstan’s larger economy has made it the center of attention for investors in Central Asia, there is no guarantee it will stay that way. With growth struck below 4% since 2015, Kazakhstan is now underperforming its Central Asian peers.

If the government drags its feet on reforms, allowing projects to languish, it risks losing out to Uzbekistan, where the new administration is actively courting businesses.

Few Kazakhs expect meaningful change anytime soon, however. «I am not going to vote because there is no point,» said a taxi driver in Almaty, the biggest city, when asked about the election in June.

Some believe Tokayev is merely an interim figurehead, installed to allow Nazarbayev to gradually transfer power and wealth to his daughter Dariga. It is anyone’s guess how she would lead: Unlike Tokayev, it is unclear whether her views align with her father’s. Though she has held various government posts, including a stint as deputy prime minister, analysts say it is difficult to credit her with any significant achievements.

Satpayev, the political expert, said an even bigger question lurks down the road. The rushed election has sparked speculation about the health of the 78-year-old Nazarbayev.

«It is not important who will be his successor,» Satpayev said. «What is more important is what will happen to the political system when he is gone.»